When you inherit a 401(k), one of the first questions people wonder about is the tax implications. With a traditional 401(k), the answer is fairly straightforward: you'll owe ordinary income tax on any money you withdraw. Because those funds were contributed pre-tax, the IRS is now ready to take its cut when the money is distributed. Understanding the tax on an inherited 401k is crucial for making smart financial decisions.

Understanding the Tax Rules for an Inherited 401k

Receiving a 401(k) inheritance can feel like a huge financial boost, but it’s critical to get a handle on the tax rules before you make a single move. The money sitting in a traditional 401(k) has never been taxed—neither the original contributions nor the decades of investment growth. That tax-deferred status ends when you, the beneficiary, start taking distributions.

When you take a withdrawal, that money is added to your total income for the year and is taxed at your regular income tax rate. It’s not a special inheritance tax; it's treated just like the salary you earn from your job. This can have a major impact on your tax bill, especially if the inheritance is large enough to bump you into a higher tax bracket.

The Core Tax Principle

Here’s a simple way to think about it: The person who owned the account received a tax break for contributing pre-tax money. The government allowed that money to grow tax-free for years, but it always intended to get its share eventually. As the new recipient, you are the one who settles that tax bill as you access the funds.

This single principle drives every decision you'll make. The specific tax impact boils down to three key factors:

- Your relationship to the original owner: Spouses get significantly more flexibility and better tax options than non-spouse beneficiaries, like a child or a sibling.

- The type of 401(k): A traditional 401(k) means withdrawals are taxable. If it's an inherited Roth 401(k), your withdrawals are completely tax-free, provided certain conditions are met.

- The timing of your withdrawals: The SECURE Act introduced strict timelines for taking the money out, which directly affects your tax planning.

The most important thing to remember is that every dollar in an inherited traditional 401(k) is potential taxable income. The key is to be strategic about how and when you take that income to manage the tax hit.

Understanding these basics is the first step toward building a smart strategy. It’s how you honor the gift you’ve received while making sure it works for your own financial goals. For a broader look at managing a windfall, take a look at our guide on what to do with inheritance money.

How the SECURE Act Changed the Rules for Inherited 401(k)s

If you’ve inherited a 401(k), the rulebook got a major rewrite a few years ago. The SECURE Act completely changed the game for how quickly most beneficiaries must take out—and pay taxes on—the money they've inherited. Understanding these changes is the first, most crucial step in making smart decisions about your inheritance.

Before this law, many non-spouse beneficiaries had a fantastic option called the "stretch IRA" (the same concept applied to 401(k)s). It allowed them to take small, required distributions over their entire life expectancy. Imagine a 40-year-old inheriting an account; they could potentially stretch those withdrawals and the associated tax bills over four decades or more. This gave the account a significant amount of extra time to grow, tax-deferred.

However, the SECURE Act, which took effect on January 1, 2020, eliminated that "stretch" provision for most beneficiaries. The old system was replaced with a much shorter timeline, completely altering the tax landscape for heirs. For a deeper dive, you can explore these insights on avoiding taxes on a 401k inheritance.

The New 10-Year Rule Explained

At the heart of these changes is the new 10-year rule. For the vast majority of non-spouse beneficiaries, this rule mandates that you must withdraw the entire balance of the inherited 401(k) by the end of the tenth year following the original owner's death.

This doesn't mean you have to take a distribution every year. It’s more of a final deadline. You have the flexibility to pull money out in chunks throughout the decade, or even wait and take it all out in a lump sum in year 10.

The catch? This compressed timeline means your tax bill comes due much faster. Instead of spreading those taxes over a lifetime, you now have to manage them within a single decade. This requires serious planning to avoid accidentally pushing yourself into a much higher tax bracket, especially if you take a large withdrawal.

The 10-year rule forces beneficiaries to deal with the tax impact of an inherited 401(k) much sooner than before. A smart withdrawal strategy over this decade is now absolutely essential to protect the value of what you've received.

Who Is Exempt from the 10-Year Rule?

While the 10-year rule is the new standard, the law carved out some important exceptions. A special group known as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDBs) can still follow the old rules. These individuals can still "stretch" distributions over their own life expectancy, which is a significant tax advantage.

The five categories of EDBs are:

- The Surviving Spouse: Spouses have the most options by far and can often just roll the inherited 401(k) into their own retirement account.

- Minor Children of the Account Owner: A minor child can take small distributions based on their life expectancy, but only until they reach the age of majority (typically 21). Once they reach that age, the 10-year clock starts ticking for them.

- Disabled Individuals: Anyone who meets the strict IRS definition of disabled can take distributions over their lifetime.

- Chronically Ill Individuals: Similar to disabled beneficiaries, those certified as chronically ill can also use the more favorable life expectancy method.

- Beneficiaries Not More Than 10 Years Younger: This applies to individuals like a sibling who is very close in age to the person who passed away.

Determining if you fall into one of these EDB categories is the very first step you need to take. If you don't—if you're an adult child, a grandchild who isn't a minor, a younger sibling, or a friend—then the 10-year rule is your new reality, and it will drive every decision you make about your withdrawal and tax strategy.

Tax Options and Strategies for Surviving Spouses

When you inherit a 401(k) from your spouse, the IRS provides a special set of options that other beneficiaries do not receive. This isn't just a technicality; it’s a recognition of your shared financial life and offers powerful ways to manage the tax on an inherited 401k.

Unlike a child or other relative who is often subject to the 10-year withdrawal timeline, a surviving spouse has far more control. The path you choose will directly impact when you pay taxes and how much longer that money can grow, so it's a decision worth understanding fully.

The Most Powerful Option: A Spousal Rollover

For most surviving spouses, the best move by far is what’s known as a spousal rollover. It's exactly what it sounds like: you move the money from your late spouse's 401(k) directly into a retirement account in your own name, like an IRA or even your own 401(k) if the plan rules permit.

The beauty of this is its simplicity and power. Once the money is in your account, it's treated as if it was always your own. Forget any deadlines tied to your spouse's age or death—the clock completely resets.

This means the funds can continue growing tax-deferred for years, even decades. You won't be forced to take Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) until you reach your own RMD age, which is currently age 73. That extra time for compounding can make a world of difference to the account's final value. To dig deeper, you can discover more insights about these special spousal 401(k) rules on Fidelity.com.

Opening an Inherited IRA

While the spousal rollover is a fantastic option, it's not the only one. You can also choose to transfer the 401(k) into a specially designated Inherited IRA (sometimes called a Beneficiary IRA). This keeps the inherited money separate from your personal retirement savings.

So, why would you ever choose this over a rollover? It comes down to one key factor: access.

If you are under age 59½ and think you might need to tap into this money, an Inherited IRA is your golden ticket. It allows you to take withdrawals without getting hit with the dreaded 10% early withdrawal penalty. For a younger spouse facing unexpected expenses, this can be an absolute game-changer.

If you choose this route, you generally have a couple of ways to handle distributions:

- The Life Expectancy Method: You can stretch distributions over your own life expectancy, recalculating each year. This provides a predictable income stream and spreads out the tax bill.

- The 5-Year Rule: This option offers total flexibility. You can take out as much or as little as you want, whenever you want, as long as the entire account is empty by the end of the fifth year after your spouse’s death.

Comparing Your Spousal Options

Ultimately, the choice between rolling the money into your own IRA or opening an Inherited IRA boils down to your age and how soon you'll need the cash. Each strategy offers a clear advantage for managing the tax on an inherited 401k.

Here's a quick comparison:

Thinking through these scenarios is a critical first step. As you build your financial plan, you may also want to explore our guide on 3 ways to minimize your tax liability, which offers strategies that can work hand-in-hand with your inheritance decisions.

Withdrawal Strategies for Non-Spouse Beneficiaries

If you're not the surviving spouse—perhaps a child, sibling, or partner—inheriting a 401(k) almost always means you're up against the 10-year rule. This isn't just a guideline; it's a strict deadline that demands a smart plan to manage the tax on an inherited 401k. How you navigate this decade-long window will directly impact how much of that inheritance you actually get to keep.

The very first move you need to make is setting up a special account called an Inherited IRA (also known as a Beneficiary IRA). This step is critical. Whatever you do, do not simply roll the 401(k) funds directly into your own personal IRA. That's a huge mistake that the IRS treats as a full, taxable distribution, which could result in a massive, immediate tax bill on the entire amount.

By properly titling an Inherited IRA—something like, "John Smith, Deceased, for the benefit of Jane Smith, Beneficiary"—you preserve the account's tax-deferred status. This is what gives you the full 10 years to figure out your next steps.

Comparing Withdrawal Approaches Under the 10-Year Rule

Once the Inherited IRA is set up, you have a big decision to make: how should you withdraw the money? You have total flexibility within that 10-year timeframe, but every choice comes with a tax consequence. Some people might opt for smaller, steady withdrawals each year, while others might find it better to wait until the last minute.

For instance, pulling out a consistent amount annually can help keep you from jumping into a higher tax bracket. On the other hand, leaving the money untouched until year 10 lets it continue growing tax-deferred for as long as possible, but you could face a much larger tax hit when you finally take that lump sum.

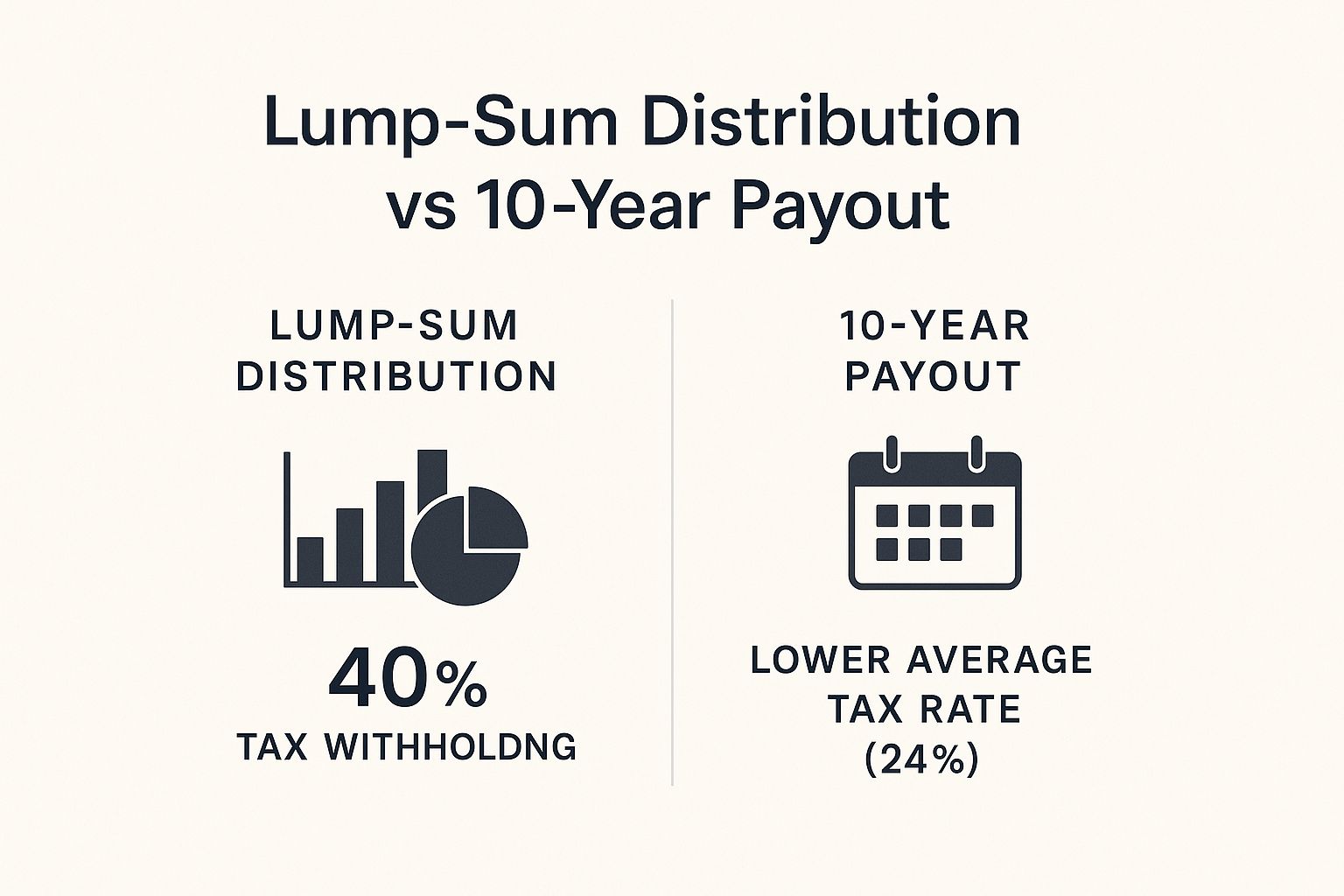

This image effectively illustrates the difference between taking it all at once versus spreading it out over the decade.

As you can see, a strategic 10-year payout can significantly reduce your overall tax rate compared to the hefty, immediate withholding that comes with a lump-sum withdrawal.

Comparing 10-Year Withdrawal Strategies

To make this more concrete, let's look at a few common approaches for a non-spouse beneficiary who inherits a $200,000 traditional 401(k). The best path depends entirely on your personal financial situation and goals.

This table shows there's no single "best" answer. Your strategy should be a direct reflection of your own financial life, not a generic formula.

Traditional vs. Roth 401(k) Inheritance

The type of 401(k) you inherit is a game-changer for your tax plan. The rules for traditional and Roth accounts are night and day, and you absolutely need to know which one you're dealing with.

- Inherited Traditional 401(k): Every single dollar you withdraw is treated as ordinary income. It gets added on top of your other earnings for the year and is taxed at your personal income tax rate.

- Inherited Roth 401(k): As long as the original account was open for at least five years, all your withdrawals are 100% tax-free. The 10-year deadline still applies, but you don't have to worry about the tax bite from your distributions.

With an inherited Roth 401(k), the strategy is often a no-brainer: let that money grow completely tax-free for as long as you can, then pull it all out just before the 10-year clock expires. For a traditional 401(k), the best approach is often the exact opposite, requiring a much more hands-on effort to manage your tax brackets year by year.

Developing a Custom Withdrawal Plan

Ultimately, your ideal withdrawal strategy is deeply personal. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution here. You need to look at your current income, what you expect to earn over the next decade, your current tax bracket, and how much you actually need the money.

Someone having a low-income year, for example, might decide to take a larger distribution to capitalize on their lower tax rate. On the other hand, if you're expecting a big promotion or bonus, you'd likely want to delay withdrawals to avoid pushing your income even higher. You can dive deeper into the nuances of retirement withdrawal strategies in our detailed guide.

The goal is simple: empty the account by the deadline while paying the least amount of tax possible. This usually means sitting down with a financial advisor to model a few different scenarios and make a truly informed decision.

Costly Mistakes to Avoid with an Inherited 401k

Handling an inherited 401(k) can feel like navigating a minefield. One wrong move could trigger a huge tax bill or stiff penalties that erode the value of the money left to you. Knowing the common pitfalls is the best way to protect your inheritance.

The biggest and most frequent mistake is simple inaction. People get overwhelmed, put the paperwork aside, and miss critical deadlines. The rules, especially the 10-year deadline for most non-spouse beneficiaries, are unforgiving. Missing it isn't a slap on the wrist; it can trigger a staggering 50% penalty on any money that should have been withdrawn.

Forgetting the 10-Year Deadline

Since the SECURE Act changed the game, the 10-year rule has become the single most important deadline for most people inheriting a 401(k). If you're not the surviving spouse, you generally have until December 31st of the tenth year after the original owner's death to empty the account. This isn't a guideline—it's a hard deadline.

For example, if you inherit a $300,000 401(k) and forget to take the money out in time, the IRS can impose a $150,000 penalty for that oversight. Just like that, one missed deadline could cut your inheritance in half. It’s easily the most expensive mistake you can make.

Taking an Immediate Cash-Out

When a significant amount of money lands in your lap, it’s tempting to cash it all out. This is almost always a massive tax blunder. When you take a lump-sum distribution from a traditional 401(k), the entire amount is added to your income for that year.

This sudden spike in income can launch you into a much higher tax bracket. A $200,000 cash-out could easily face a combined federal and state tax hit of 30-40% or more, depending on where you live and your other earnings. That "windfall" quickly turns into a huge, unexpected tax liability.

Incorrectly Titling the Inherited IRA

This one is technical, but getting it wrong is a disaster. When you move the money from the inherited 401(k), it must go into a specially titled Inherited IRA, sometimes called a Beneficiary IRA. Before you do anything, it's a good idea to understand your rights and protections regarding IRS actions on your 401k.

The account title has to be very specific, something like: "[Deceased's Name], for the benefit of [Your Name], Beneficiary."

Mistakes here can lead to a couple of terrible outcomes:

- Rolling it into your own IRA: If you're not the spouse and you mistakenly move the funds into your personal IRA, the IRS treats it as a full, taxable distribution. The entire amount becomes taxable income, right then and there.

- Simple Titling Errors: Even small mistakes in the account name can cause major administrative headaches and potential tax problems later on.

The proper titling of an Inherited IRA is what keeps its tax-deferred status intact. It’s the legal step that gives you the full 10-year window to plan your withdrawals and manage the tax impact. Get it wrong, and you’ve essentially just cashed the whole thing out.

Misunderstanding Your Beneficiary Status

The IRS does not treat all beneficiaries the same. The rules for a surviving spouse are completely different—and much more flexible—than those for a non-spouse, like a child, sibling, or partner. A common error is for a non-spouse to assume they can do what a spouse can, like rolling the 401(k) into their own retirement account.

Likewise, an adult child might not realize the 10-year rule applies to them, while a minor child could qualify as an "Eligible Designated Beneficiary" and get a different set of options. The very first thing you should do is confirm your exact beneficiary category. Acting on assumptions is a surefire way to run into tax trouble.

Answering Your Inherited 401(k) Tax Questions

Even after you understand the rules, inheriting a 401(k) can leave you with many specific questions. The details really matter, and one small misunderstanding could turn into a costly mistake. Let's walk through some of the most common questions people have about the tax on inherited 401(k)s to provide clarity.

Think of this as a final sanity check. Getting these common sticking points straight is the key to making a smart financial move with confidence.

Do I Have to Take Money Out Every Single Year Under the 10-Year Rule?

This is perhaps the biggest point of confusion with the 10-year rule. For most non-spouse beneficiaries, the answer has been a moving target, but the IRS has provided some guidance. The rule states the entire account must be empty by the end of the 10th year, but whether you must take money out each year is the tricky part.

It all hinges on whether the original account owner had already started taking their own Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs).

- If the original owner had NOT started RMDs: You are generally in the clear. You have the full 10-year window to drain the account, and you can do it on whatever schedule works for you. Take a little each year, take a few lump sums, or wait and take it all out in year 10—it's your call.

- If the original owner HAD started RMDs: This is where it gets more complicated. The latest IRS interpretations suggest you might have to keep taking annual payments (based on your own life expectancy) and still empty the whole account by the 10-year deadline.

Frankly, this area of tax law has been murky since the SECURE Act was passed. Because the guidance could shift again, it is absolutely critical to talk to a tax professional to get the latest rules before you settle on a withdrawal plan.

What Happens if I Inherit a Roth 401(k) Instead?

This is a completely different scenario. Inheriting a Roth 401(k) is a fantastic tax advantage and makes your planning much simpler. The original contributions were made with after-tax money, which means any withdrawals you take are completely tax-free.

However, you're not totally off the hook. There are two important rules to remember:

- The 5-Year Rule: For your withdrawals to be officially "qualified" (and thus tax-free), the original Roth account must have been opened for at least five years.

- The 10-Year Rule: For most beneficiaries, you still have to empty the entire account within that decade.

The strategy here is usually straightforward. You can let the money grow, completely untaxed, for nearly 10 years and then pull the entire balance out right before the deadline. You won't owe a dime in federal income tax.

Inheriting a Roth 401(k) removes the primary challenge of managing your tax bracket. The focus shifts from tax planning to simply maximizing tax-free growth within the mandatory 10-year window.

Can I Just Roll an Inherited 401(k) into My Own IRA?

This is a crucial point that trips up many people. The answer is a hard no, unless you are the surviving spouse. Only a spouse has the special privilege of rolling inherited 401(k) funds directly into their own IRA or other retirement account.

If you're a non-spouse beneficiary—a child, a sibling, a partner—you cannot mix inherited retirement money with your own. You must move the money into a special "Inherited IRA," which is sometimes called a Beneficiary IRA.

If you mistakenly move the money into your personal IRA, the IRS considers that a full distribution. The entire amount immediately becomes taxable income, and you’ll be hit with a massive tax bill, completely wiping out the tax-deferred benefit you were trying to preserve.

Is an Inherited 401(k) Safe from Creditors?

Creditor protection for inherited accounts isn't as simple or guaranteed as it is for your own retirement funds. The level of protection you get often depends on the account type and your state's laws.

A significant 2014 Supreme Court ruling established that inherited IRAs do not get the same strong federal bankruptcy protection as personal retirement accounts. That means if you move the 401(k) funds into an Inherited IRA, that money could be vulnerable to creditors.

On the other hand, funds you leave in the inherited 401(k) plan itself (if the plan allows it) might have stronger protection under federal ERISA law. The rules also vary dramatically from state to state; some offer much better protection for inherited accounts than others.

If protecting these assets is a major priority for you, it's vital to speak with a legal professional who specializes in estate planning and asset protection before you make any moves.

Managing an inheritance is just one piece of a larger financial picture. At Commons Capital, we specialize in helping high-net-worth individuals and families handle complex financial situations to achieve their long-term goals. If you're navigating an inheritance and want to ensure it's integrated seamlessly into your wealth strategy, we invite you to connect with our team. Learn more about how we can help at https://www.commonsllc.com.