Understanding the taxes on a trust can often feel overwhelming, but it essentially comes down to a single, critical question: who is responsible for paying the tax? The answer directly depends on the type of trust in question.

In some cases, the individual who established the trust, known as the grantor, handles the tax obligations on their personal return. This is common for structures like a revocable living trust. In other scenarios, the trust operates as a distinct taxable entity, filing its own returns and paying its own taxes, which is typical for most irrevocable trusts. This fundamental distinction dictates how income, estate, and gift taxes are managed, forming the cornerstone of effective trust tax planning.

How Trust Taxation Really Works

A trust is an incredibly powerful financial tool, not just for passing wealth to the next generation but also for managing and protecting your assets today. To leverage its full potential, a clear understanding of the tax implications is non-negotiable.

Every trust involves three key players whose roles are foundational to its operation and taxation:

- The Grantor: The individual who creates the trust and transfers assets into it.

- The Trustee: The manager—a person or institution responsible for administering the trust's assets according to the terms of the trust document.

- The Beneficiary: The person, people, or entity (like a charity) who will receive the benefits from the trust, whether that's income or the assets themselves.

The interplay between these roles, combined with whether the trust is revocable or irrevocable, determines the tax consequences. Before establishing a trust, it's wise to consider if it aligns with your financial objectives. Our guide on when you may need a trust can provide valuable clarity on this decision.

Grantor vs. Non-Grantor Trusts: The Core Distinction

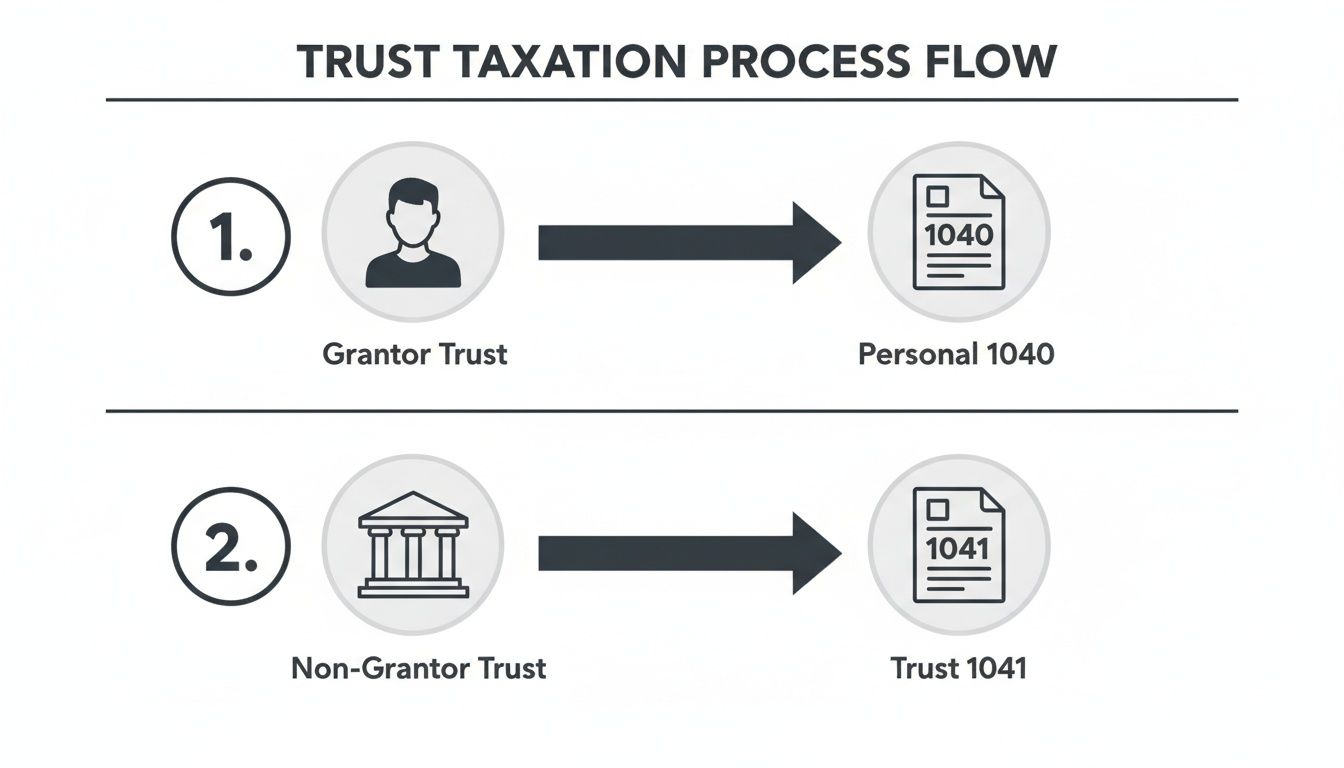

The landscape of trust taxation is divided into two primary categories: grantor trusts and non-grantor trusts. Grasping this difference is the first step to mastering how trust taxes work.

In a grantor trust, the creator retains a significant degree of control. Consequently, the IRS disregards the trust for income tax purposes. All income, deductions, and credits generated by the trust's assets flow through directly to the grantor’s personal tax return (Form 1040). It operates much like a pass-through entity, with the revocable living trust being a prime example.

Conversely, a non-grantor trust is treated as a completely separate taxpayer. It requires its own taxpayer identification number (TIN), files a dedicated tax return (Form 1041), and pays taxes on any income it retains and does not distribute to beneficiaries. This is the standard for irrevocable trusts, where the grantor has permanently relinquished control over the assets.

Key Tax Differences at a Glance

This table breaks down the fundamental distinctions, highlighting the critical planning considerations.

As illustrated, the choice between a grantor and non-grantor structure has profound implications, impacting not only annual income taxes but also long-term estate tax planning. One offers flexibility, while the other provides powerful tax-shielding advantages.

The Two Pillars of Trust Taxation

To truly understand how trusts are taxed, you must first grasp the fundamental difference between Grantor and Non-Grantor trusts.

This is not merely legal jargon; it is the core distinction that determines who pays the tax, which forms are filed, and how the trust functions within a broader financial strategy. Mastering this concept is step one.

Think of a Grantor Trust as a direct financial extension of its creator. Because the grantor maintains certain controls—such as the power to revoke the trust or change beneficiaries—the IRS essentially sees through it for income tax purposes, treating it as a "disregarded entity."

In practice, this means all income, gains, and losses from the trust's assets are reported directly on the grantor's personal Form 1040. The trust itself pays no income tax. The classic revocable living trust, which typically uses the grantor's Social Security Number, is a perfect example. While it doesn't offer income tax savings, it is an excellent tool for avoiding probate and managing one's affairs.

The Grantor Trust Explained

So, what "controls" keep the tax liability with the grantor? The IRS is specific about the powers that define a grantor trust:

- Power to Revoke: The ability to dissolve the trust and reclaim the assets.

- Control Over Beneficial Enjoyment: The power to decide who receives distributions and when.

- Administrative Powers: The ability to borrow from the trust without adequate interest or security.

- Income for the Grantor's Benefit: If trust income can be distributed to the grantor or their spouse, used to pay their life insurance premiums, or used to satisfy their legal obligations.

If any of these powers exist, the income tax responsibility remains with the grantor. This is a critical point for anyone developing a foundational estate plan.

The Non-Grantor Trust: A Separate Taxpayer

Now, consider the alternative. A Non-Grantor Trust is recognized by the IRS as a completely separate taxpayer—its own financial entity. This occurs when the grantor relinquishes significant control, making the trust irrevocable.

As a standalone entity, a non-grantor trust must obtain its own Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN). More importantly, it is required to file an annual tax return on Form 1041, the U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts. This is where tax planning becomes essential.

Here's the kicker for non-grantor trusts: their tax brackets are brutally compressed. In 2024, a trust hits the top federal income tax rate of 37% after earning just $15,450.

This income threshold is a small fraction of what an individual must earn to reach the same bracket, making proactive tax management crucial. If a trust accumulates income instead of distributing it, it can face a substantial tax bill very quickly.

This reality drives many sophisticated strategies for high-net-worth families. The objective often becomes carefully timing distributions to beneficiaries in lower personal tax brackets, effectively shifting income out of the trust's high-tax environment.

Understanding the Fiduciary Tax Return: Form 1041

When a non-grantor trust generates its own income, it becomes an official taxpayer and must file Form 1041, the U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts.

This form is the trust's equivalent of a personal Form 1040. On it, the trustee reports all income—such as interest, dividends, and capital gains—and subtracts the allowable costs of administering the trust.

Allowable Deductions for a Trust

Like any taxpayer, a trust can reduce its taxable income by taking deductions for ordinary and necessary expenses related to its administration.

Common deductions include:

- Trustee Fees: Compensation paid to the trustee for managing the trust.

- Professional Fees: Payments to accountants for tax preparation or attorneys for legal counsel.

- Investment Advisory Fees: Costs associated with professional management of the trust's portfolio.

- State and Local Taxes: Taxes paid directly by the trust, such as property taxes on real estate it holds.

This simple flowchart illustrates the core filing difference.

As shown, a grantor trust's income flows onto the grantor's personal 1040. A non-grantor trust, however, must file its own separate Form 1041.

The Role of Distributable Net Income (DNI)

After calculating total income and subtracting initial deductions, the next step is determining Distributable Net Income (DNI). DNI is a crucial concept that serves two primary functions: it establishes the maximum possible distribution deduction for the trust, and it determines the amount and character of taxable income passed through to the beneficiaries.

Think of DNI as the total pool of income available for distribution. When the trustee distributes a portion of this income to a beneficiary, the corresponding tax liability goes with it. This mechanism prevents the same income from being taxed twice—once at the trust level and again when the beneficiary receives it.

The Income Distribution Deduction

The most powerful tool for reducing a trust's tax bill is the income distribution deduction. The principle is straightforward: when a trust distributes income to its beneficiaries, it can deduct that amount from its taxable income. The deduction is limited to the trust's DNI for the year.

The trustee then issues a Schedule K-1 to each beneficiary, detailing the type and amount of income they received. The beneficiary uses this K-1 to report the income on their personal tax return. The trust is then only taxed on any income it retained.

Key Takeaway: This pass-through system is the central strategy. It allows you to bypass the trust's compressed tax brackets by shifting the tax burden to beneficiaries, who are often in a much lower tax bracket.

This complexity explains why high-net-worth families increasingly seek certainty in their financial planning. The global tax insurance market has seen explosive growth, as noted in one firm's year-end report, which processed a record 1,917 global tax submissions—a 25% increase from the prior year. This demand is driven by the need to lock in the tax consequences of complex trust restructurings, especially given the harsh reality of U.S. trust tax rates. You can read the full report on the tax insurance industry for more details.

Beyond Income Tax: Estate and Gift Tax Rules

While annual Form 1041 filings are a key aspect of trust administration, the most significant impact for high-net-worth families lies in strategic management of federal transfer taxes. This includes the estate tax, the gift tax, and the generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax.

This is where the irrevocable trust truly excels. By transferring assets into a properly structured irrevocable trust, you make a completed gift. This action removes those assets—and all their future appreciation—from your taxable estate permanently. Over time, this can result in substantial tax savings for your heirs.

The Lifetime Gift and Estate Tax Exemption

Central to this planning is the federal gift and estate tax exemption. This is a lifetime allowance from the IRS that lets you transfer a significant amount of wealth to others—during your life or at your death—without incurring transfer taxes. For 2024, this exemption is a substantial $13.61 million per person.

Each time you make a taxable gift, such as funding an irrevocable trust, you use a portion of this lifetime exemption. For example, if you transfer $5 million in stock to a trust for your children, you would file a gift tax return (Form 709) to report it. You wouldn't owe tax; instead, your remaining lifetime exemption would decrease by $5 million. The strategy is to use this exemption to move high-growth assets out of your estate, allowing them to appreciate tax-free for your beneficiaries. Our guide on how to minimize estate taxes delves deeper into these techniques.

Understanding the Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax

To close a loophole where families could bypass a generation of estate taxes by leaving assets directly to grandchildren, Congress introduced the Generation-Skipping Transfer (GST) Tax.

The GST tax is a separate tax imposed on transfers to "skip persons"—typically grandchildren or individuals at least 37.5 years younger than you (who are not your spouse). This tax is levied at the highest federal estate tax rate.

Fortunately, you also have a GST tax exemption, which is equal to the lifetime gift and estate tax exemption. Effective estate planning involves carefully allocating this exemption to your trusts to shield them from this punitive tax for multiple generations.

Real-World Application: Consider an entertainer whose brand and intellectual property are rapidly increasing in value. By placing these assets into a GST-exempt trust, all future growth occurs outside their taxable estate. This protects the wealth not just for their children but for their grandchildren as well, without triggering the additional layer of GST tax.

Specialized Trusts for Tax Efficiency

For specific goals, specialized irrevocable trusts are designed to maximize tax efficiency. One of the most effective tools is the Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (ILIT).

Here's how it works:

- You establish an ILIT, and the trust purchases a life insurance policy on your life.

- Crucially, the trust is both the owner and the beneficiary of the policy.

- Upon your death, the life insurance proceeds are paid directly to the trust.

Because you did not personally own the policy, the entire death benefit passes to the trust completely free of federal estate tax. This provides your family with a source of tax-free liquidity to pay estate taxes, settle debts, or cover other expenses without being forced to sell assets like a family business or real estate. It's a classic example of how a well-structured trust can be the cornerstone of a solid estate plan.

Tax laws and exemption amounts are subject to change. It is essential to stay informed about recent changes to the estate tax exclusion to ensure your long-term wealth strategy remains effective.

If you believe mastering federal rules is enough, you've only won half the battle. The complex and often-overlooked world of state taxation can create unexpected liabilities that derail even the most carefully crafted plans.

Each state has its own rules for taxing trust income, creating a tangled web of potential obligations. States establish tax jurisdiction through "nexus," or a connection to the trust.

How States Get Their Hooks in a Trust

Unlike an individual, a trust can be considered a "resident" for tax purposes in multiple states simultaneously. A state can typically tax a trust's accumulated income if any of the following connections exist:

- The Grantor: Many states claim jurisdiction if the trust's creator was a resident, especially if the trust became irrevocable upon their death.

- The Trustee(s): The physical location of the trustee is a common basis for state taxation.

- The Beneficiaries: An increasing number of states tax trust income based on the residency of the beneficiaries.

- Trust Administration: The location where the trust's affairs are managed can also trigger a tax obligation.

This multi-faceted approach means a single trust could have filing requirements in New York, Florida, and California simultaneously. Navigating this complexity makes professional guidance essential.

Dodging the Tax Man in High-Tax States

Residents of high-tax states like California and New York face significant challenges from these state trust residency rules. This has led to the development of sophisticated strategies designed to legally reduce or eliminate state-level income taxes.

One popular tool is the Incomplete Gift Non-Grantor (ING) Trust. This is a cleverly engineered trust designed to be a non-grantor trust for state tax purposes (shifting the tax burden away from the grantor in the high-tax state) while remaining a grantor trust for federal purposes. When structured correctly, an ING trust can result in substantial state tax savings, but it requires meticulous setup and administration.

Going Global: Navigating International Trust Taxes

For clients with a global footprint—such as international entrepreneurs or families with assets in multiple countries—the complexity increases exponentially. The introduction of foreign assets, trustees, or beneficiaries brings foreign reporting requirements and international tax treaties into play, where missteps can lead to severe penalties.

Global tax attitudes are also shifting, directly impacting wealth planning. The 2025 OECD Public Trust in Tax survey reveals significant differences in perception. For instance, in 60% of Asian countries, a majority believe their tax money is used for the public good, compared to only 30% in Western Europe.

This public sentiment often translates into more favorable tax laws. It is no coincidence that many Asian jurisdictions tax undistributed trust income at a moderate 15-20%, a stark contrast to the U.S., where combined federal and state rates can exceed 50%. You can learn more about how these global tax perception trends impact wealth management.

Furthermore, new global minimum taxes under Pillar Two—establishing a 15% effective tax rate—are making the world of international wealth more interconnected. High-net-worth individuals must now navigate a global matrix of tax codes, not just a single country's rules.

Actionable Strategies to Minimize Your Tax Burden

Understanding the rules of trust taxation is one thing; using them to your advantage is another. Proactive management is essential to preserving wealth for your family.

The most direct strategy is to be strategic with distributions. Since trusts face high tax rates at low income thresholds, allowing earnings to accumulate can be a costly error. By distributing income to beneficiaries in lower personal tax brackets, you shift the tax burden to a more favorable environment.

Strategic Income and Expense Management

Effective tax planning involves more than just well-timed distributions. It requires year-round discipline in managing income and expenses to minimize the trust's taxable footprint.

One powerful strategy is to make charitable donations directly from the trust. A trust can receive an unlimited deduction for gross income paid to a qualified charity, potentially eliminating its taxable income entirely. This is often more tax-efficient than a beneficiary receiving the income, paying tax on it, and then making a personal donation.

Timing capital gains is another critical area. A skilled trustee can harvest capital losses to offset gains or time the sale of a highly appreciated asset to a year when the trust or its beneficiaries are in a lower tax bracket. This requires close coordination between the trustee and the investment advisor.

Advanced Trust Modification Techniques

Sometimes, an existing trust's terms become outdated due to changes in laws or family circumstances. In such cases, advanced techniques may be necessary.

One technique is trust decanting. This process allows a trustee to "pour" the assets from an older, inflexible irrevocable trust into a new one with more favorable terms. Decanting can be a game-changer for modernizing trusts to address new state tax laws or evolving family needs.

Another sophisticated approach is using specialized trusts from the outset. For example, an Intentionally Defective Grantor Trust (IDGT) is a powerful planning tool. It is structured as a grantor trust for income tax purposes (so the grantor pays the tax) but is excluded from the grantor's estate for estate tax purposes.

Scenario Example: A grantor transfers $2 million of high-growth stock into an IDGT. For estate tax purposes, this is a completed gift, and all future appreciation occurs outside the grantor's taxable estate. However, the grantor remains responsible for the income taxes. This allows the trust's assets to grow unburdened by taxes, effectively providing an additional tax-free gift to the beneficiaries each year.

These strategies are complex and require expert guidance. By working with a team of advisors, you can implement these techniques to effectively manage the taxes on a trust and secure your family's financial future.

Common Questions About Trust Taxes

As you delve into trust administration, several practical questions often arise. Here are answers to some of the most common inquiries from grantors, trustees, and beneficiaries.

Does a Revocable Trust Pay Taxes?

No, a revocable trust itself does not file its own tax return or pay income taxes. It is a grantor trust, which functions as a pass-through entity for tax purposes.

All income generated by the trust's assets—such as dividends, interest, and capital gains—is reported directly on the grantor's personal Form 1040. The IRS essentially disregards the trust and attributes the income to the grantor. This simplifies tax filing but provides no income tax savings.

Who Is Responsible for Filing the Tax Return for a Trust?

The trustee is legally responsible for managing the trust, which includes filing all required tax returns.

For a non-grantor trust, the trustee must file Form 1041, the U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts. The trustee is also responsible for issuing a Schedule K-1 to any beneficiary who received an income distribution during the year. The K-1 informs the beneficiary of the amount and character of income they must report on their personal tax return.

Key Responsibility: A trustee's fiduciary duty is a serious commitment, and accurate, timely tax compliance is a core component. Failure to comply can result in significant penalties for the trust, making this one of the most critical roles in trust administration.

Does a Trust Need Its Own Tax ID Number?

In many cases, yes. An irrevocable trust (a non-grantor trust) is considered a separate taxable entity by the IRS and must obtain its own Employer Identification Number (EIN).

A revocable (grantor) trust, however, does not need an EIN. It uses the grantor's Social Security Number for tax reporting, as all income flows directly to the grantor's personal return. This is a key distinction between the different types of trusts.

How Can a Trust Reduce Its Taxable Income?

A trust can lower its tax bill through strategic planning in a couple of key ways:

- Claiming Deductions: A trust can deduct ordinary and necessary expenses incurred in its administration, such as trustee fees, legal and accounting fees, and investment management fees.

- Making Distributions: This is the most effective strategy. Distributing income to beneficiaries shifts the tax liability from the trust, with its compressed tax brackets, to the individual beneficiaries, who are typically in a lower tax bracket.

By strategically timing and sizing income distributions, a trustee can significantly reduce the overall tax impact on the trust's earnings, preserving more wealth for its intended beneficiaries.

Navigating trust taxation is complex and not something to leave to chance. The team at Commons Capital specializes in creating intelligent financial strategies for high-net-worth individuals and families, ensuring your wealth is managed with maximum efficiency. Learn how our advisory services can help you achieve your financial goals.